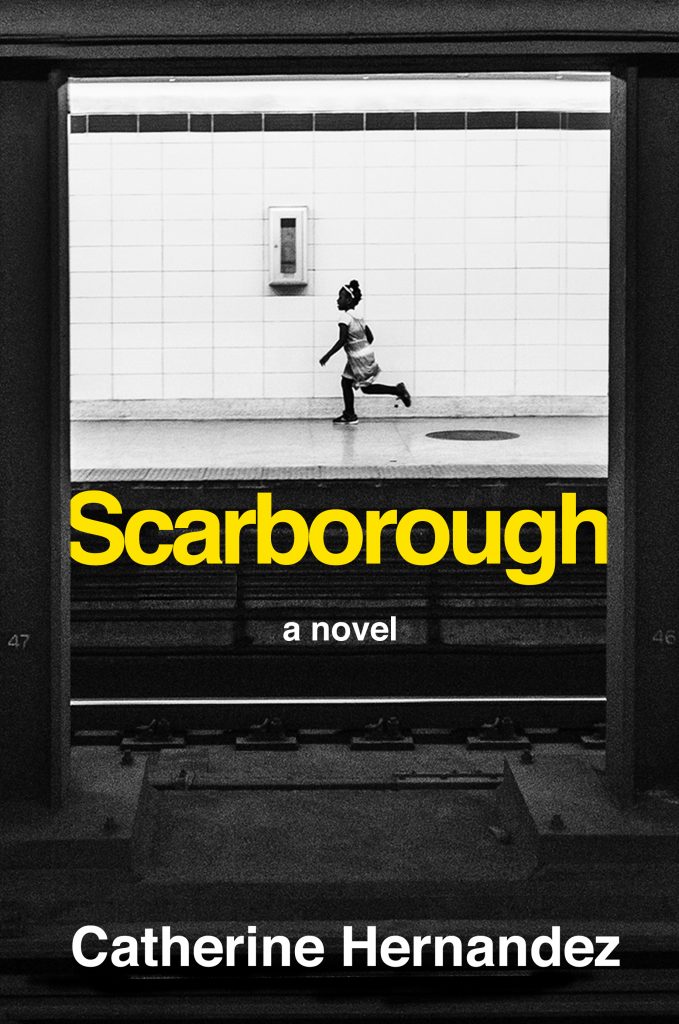

Scarborough, Catherine Hernandez, 254 pgs, Arsenal Pulp Press, arsenalpulp.com, $17.95

Scarborough. The book’s title, named after the massive amalgamated suburb to the east of Toronto’s downtown, will evoke a range of feelings in any Torontonian reader when uttered. For some, Scarborough represents an “out there,” a distant land that is not quite Toronto — surely not as cosmopolitan, wanting for culture, fine eateries, and rapid transit. A place many have never visited. For others, it’s home — a place where you hear ten languages in ten minutes, where chaos is a sign of calm, where everybody’s histories, however different, hungrily intertwine.

It’s this second Scarborough that is not simply the background, but in fact the refracted protagonist of the first full-length fiction release by playwright, performer, and activist Catherine Hernandez. Told through the eyes of at least a dozen characters, the novel explodes stereotypes about Scarborough’s working poor, disabled, and racialized folks by giving the reader access to the psychic pain and hyperspecific logics of survival that motivate her characters.

Although there are many lives that intersect throughout the novel, the action revolves around the literacy centre at Rouge Hill Secondary School, where a young Muslim worker has to negotiate the extreme poverty, hunger, and violence affecting the community she serves while managing the cold, unfeeling demands of her supervisors.

At this centre for children and parents, tensions around race and culture both harden and dissipate. Parenthood and family, always rife with as much pain as love, emerge as the arena where difference is hammered out or reigned in. A friendship forms between the children of an overworked Filipina cosmetologist and a stoic, resourceful Indigenous woman living in a nearby shelter — and thus, between the mothers, too. Meanwhile, an incapable dad refuses to acknowledge that the only people able willing to help him and his daughter also belong to the groups he spent years terrorizing as a skinhead youth.

Indeed, Hernandez goes deeper than most writers dare when it comes to the complexities of racial and cultural violences, unafraid to unpack the explicit and implicit prejudices that inform her characters’ behaviours, white and racialized alike. There are many disheartening moments in this book, where the odds are stacked against just about everyone. But for each instance of unnecessary hostility or institutional suffocation, there are slices of solidarity across social position and background, episodes of superhuman resilience.

For a place so full of magic, culture, and frenzy, it’s amazing that nobody has put out a book about Scarborough yet — but indeed, that’s telling of the way the sub-city is excluded by literary and artistic powerbrokers. Catherine Hernandez takes painstaking care to do the place justice, including thorough research and collaboration to ensure cultural accuracy, an abiding commitment to nuance and a patience with the limits of writing to represent the fullness of experience.

Most importantly, Hernandez writes not from the vantage of “them over there” but from “us” and “we.”

“We, the brown kids with one and one-half parents, with siblings from different dads we only see in photos; we who call our Grandmothers mom; we who touch our Father’s hands through Plexiglas.”

This is a crucial book for Toronto, and a shining example for writers concerned with the cultural tensions of the now. (Jonathan Valelly)