The uncertain future of Robert Thomas Payne, homeless zinester

There are two Robert Thomas Paynes in Toronto. One is a writer. The other does a lot of walking. One has managed to conjure up some buzz for himself. The other, at times, is virtually invisible. One is a poet, an editor, and a voice for the neglected. The other doesn’t like to go to bed unless he has earned enough money to make it through tomorrow.

“There is my real life, and my virtual life,” explains Payne while sitting on a coffee shop patio drinking ‘juice’ from a plastic bottle. “My real life is spent mostly outside, mostly walking. My virtual life, it’s not that bad.”

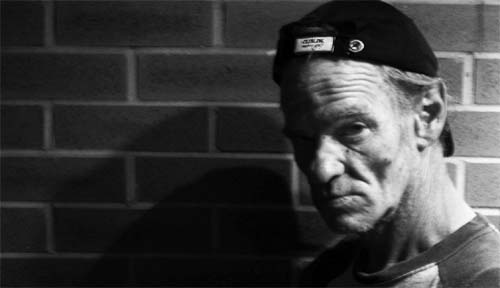

The real Robert Thomas Payne has been living on the streets since 2006. You can see it in his calves, which are hulking from all the walking. He has small boyish eyes on an aged, weary face. His hair is almost completely grey. Payne vacillates between looking childlike and older than his almost 50 years.

He wakes up everyday in a narrow alley next to a downtown bar. His assignment each day is to make $20 before he goes back to bed. In order to reach his goal, Payne walks around the streets of Toronto with photocopies of a zine that he tries to sell to strangers. He will not ask for spare change, he will not sit on a corner with a cup and a sign.

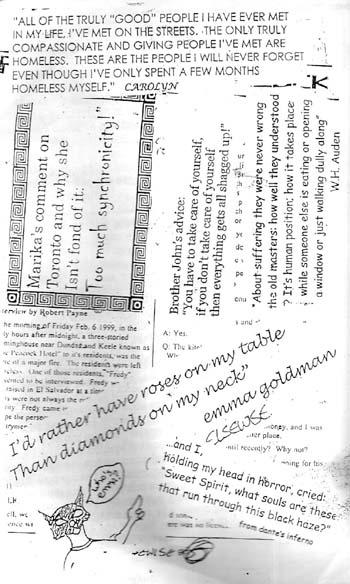

Tonight, the real Payne is working with two zines. One is called St. Elsewise, his flagship brand. It is a collection of work — stories, poems, jokes and pictures — all written and drawn by Payne and other homeless people living in Toronto.

“Unfortunately, the zine is about 75% my writing, and the rest I collect,” says Payne, lamenting his inability to coax more work from others.

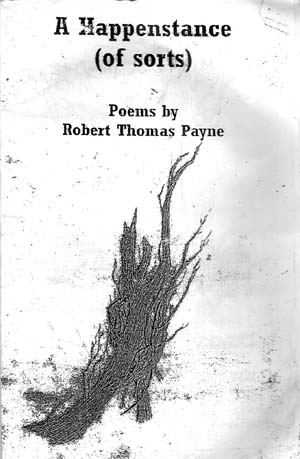

The other zine is A Happenstance (of sorts), a collection of poems written by Payne. His poems are inspired by his life on the streets, and offer windows into both his life, and a side of the city most of us don’t see. At the same time there are elements of hope and humour in Payne’s writing.

On this night you can buy a copy of St Elsewise or A Happenstance for whatever you want to pay. You just need to run into Payne.

He likes to work on the West side of downtown, outside the Tim Horton’s at the generally bustling intersection of King and John, or outside For Your Eyes Only, a gentlemen’s club on King Street between Spadina and Bathurst. If he is not at one of those locations then he is wandering the streets.

***

Robert Payne was born in Newfoundland. His father was a sailor, and so was his grandfather. When Payne turned 16 he joined the Merchant Marines and worked during the summers. He grew up all over Canada, but spent his high school years in Toronto where he attended Bloor Collegiate. After graduating, Payne went to The University of Toronto for two years where he majored in theatre and minored in archeology. He left school when he was 21, he says, because he was getting lots of work as an actor, which at the time was his goal.

In 1996 Payne began volunteering at St. Christopher’s, a neighbourhood centre in the West End of the city that helps less advantaged individuals, families and groups. “That was when I was having my couple of crazy years, breaking up with the wife, kind of wondering what was I doing with my life,” he says. Volunteering was Payne’s way of contributing, of giving back. He alludes to a rough childhood, and knowing something about hardships.

One of Payne’s closest friends, another aspiring writer by the name of Michael Paul Martin, was also volunteering at St. Christopher’s House. In 1998 a worker there had the idea of starting a newsletter that would be circulated within the building. Payne and Martin decided to take on the project and founded The Street Post.

The Street Post was what St. Elsewise is now: A collection of stories, jokes and pictures produced by street people. Payne and Martin would collect the material and assemble the zine. Eventually they were able to secure a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts and begin printing a thousand glossy issues every three or four months. What started as an in-house newsletter was growing.

Then, Payne says things went “titties up.” In 2006 The Street Post’s run ended, and because when it rains it pours, Payne found himself on the streets. At the time his main source of income was through acting and temp jobs. He was never paid for his work on the Street Post, which was an extension of his volunteer work. One day the acting and temp jobs just stopped. Payne had lived on the street before, but had always managed to pull himself off after a few months. This time would be different.

Nonetheless, Payne decided to continue on with the project of writing and collecting stories by and of the homeless. As he says of that time: “If that is the way I had to do it then that is what I would do.” He began collecting work, cutting and pasting, photocopying and stapling. St. Elsewise was the result.

“It’s about creating something, and other people being interested in what you created. That is why I try to sell my zines face-to-face. I can’t tell you how much joy I get out of it.”

It’s been nearly four years since Payne started St. Elsewise and he is still writing and gathering work from others who live on the street. He takes the task seriously. Payne claims he has kept all the originals of all the work that has ever been handed to him from someone else that lived on the street. He says he knows a lot of street people who have passed away, and feels a responsibility to hold onto anything that documents that they were here.

His biggest failure is not being able to convince others who live on the street to do more than contribute here and there. He wants them to take up writing, or any other form of art. And he wants to see them go through the process of photocopying their own issues of St. Elsewise and try to sell them. “It’s about creating something, and other people being interested in what you created,” he says. “That is why I try to sell my zines face-to-face. I can’t tell you how much joy I get out of it.”

If it were up to Payne he would be able to share the sense of worth he gets from his endeavours with other street people. So far he has not been successful. “That is probably the thing I am most disappointed about.”

And so Payne remains Toronto’s only homeless publisher. As such, Payne has had some high profile clients. He says he sold a copy of The Street Post to Jay-Z for an American dollar. He exchanged a copy of his zine to Leonard Cohen for a few bucks and a bag of peanuts. Paris Hilton traded a salad bowl for a copy of St. Elsewise — she thinks the zine is hot. Payne thinks a salad bowl is a silly thing to give a homeless man, but he was able to sell it and she’s a nice girl. Walter Gretzky has bought several copies of St. Elsewise over the years and is always disappointed to find out Payne is still living on the streets. Adrienne Clarkson also stopped to get a copy of The Street Post way back when.

She was so impressed she invited Payne and Martin to talk about their zines at Blue Metropolis, Montreal’s literary festival, two years in a row. Unfortunately the added attention is what Payne thinks led to the “upping” of The Street Post’s “titties.” As he tells it, The Street Post was just supposed to be an in-house newsletter and the St. Christopher’s House was uncomfortable with the attention it was getting as something more. Ultimately, they pulled the plug.

More recently, cbc.ca did a couple short pieces on Payne for Connect with Mark Kelly, and Payne says the Globe and Mail paid him a visit for their own interview, though, as of press time, a story has yet to surface from that encounter. Then there is the documentary on Payne that has recently wrapped-up filming and is being edited.

Payne’s been profiled and observed, but that hasn’t changed his circumstances or his attitude: he’s still on the streets. After sitting and talking for a while, we leave the coffee shop patio and wander over to the sidewalk outside For Your Eyes Only. They know him there, the bouncers, and some of the dancers. Not as a customer. They know him as Robert Thomas Payne, the guy who is always trying to sell his writing. Nobody tries to stop him. The wall beside the club’s door used to have one of his poems scribbled across it before a new tenant moved in and painted it over. You can still make out some of the words if you look closely.

Payne is a few bucks short of his $20 quota for the day. He doesn’t want to give up, but he’s tired. It was a long hot day. He stands there, looking for someone to sell his zine to, but he knows everyone around him and they’re not interested. Payne says he should still try to approach a few more people, but he looks like he is ready to pack it in. The night is getting that feeling. I ask him what he would do if someone offered him a job, as a dishwasher or something else that would let him make enough money to get off the streets. Would he take it? “No,” he says immediately. “I got myself into this mess, and I am going to get myself out of it. And I am going to do it through art.”

It’s at once a naïve and noble answer. For his sake, I hope he is right.

Vakis Boutsalis gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Ontario Arts Council’s Writers’ Reserve Program.