Liz Worth investigates the survival of zines and finds that they’re more important than ever

“In web-centric world of 1,001 blogs, zines still making a scene,” went a Fall 2010 article that ran in the Winnipeg Free Press. The story — inspired by Canzine West, the Broken Pencil-hosted Vancouver zine fair — quoted zinester Claire Heslop, creator of The Sun Shines on it Twice, who had initially traded in zine-making for blogging, but ended up abandoning the digital format to return to her original passion: zines.

“[Blogging] didn’t really work for me, I didn’t get any enjoyment out of it, it didn’t feel satisfying,” Heslop said. “It’s not the same as having a real, small, colourful and crazy interactive piece of something that somebody made by hand for you.”

The death of the zine has been repeatedly declared. Even Broken Pencil screamed out from its 12th issue, in the spring of 2000, that it was the end of zines: “Zines are dead,” ran the headline of an article by Chris Yorke which asked, “What killed zines?”

As it turned out, nothing killed zines. Broken Pencil is now entering its 15th year of publishing. There are very healthy annual zine fairs across North America including Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Halifax, suburbs and small towns. No matter how dire the predictions, the zinester spirit has remained strong. Indie creators continue to maintain their stubborn insistence on self-published, handmade creations. As a result, zines are very much alive and filling the same crucial, cultural roles they always have.

So what gives? For a medium that’s supposedly dying, the zine has been, and remains, an important piece of Canada’s independent culture scene. In fact, it could even be argued that zines are more of an accepted and established part of the overall arts scene in North America than ever before. Galleries are exhibiting them, major libraries are collecting them and universities teach classes on them. So the question is, how did the zine go from media darling to nearly deceased to an accepted, maybe even vital, component in the arts landscape? We decided to take a look at the role zines have played in the last three decades and find out.

The ’80s

When Toronto artist GB Jones first started working on zines in the 1980s, she began by helping her friend and Fifth Column band mate Caroline Azar with Hide, a zine that was accompanied by a compilation cassette tape. Being in a touring band, Hide gave Jones and Azar a way to keep connected to bands they’d meet throughout the Ontario circuit by inviting them to contribute a recording for the Hide compilation.

“Fanzines were truly a source of information,” Jones says. “They had information on musicians and photographers and other fanzines you might not have heard about, and that you definitely would not have read about in mainstream magazines. You can’t really even estimate how important that was.”

Although zines first emerged in the 1930s through science fiction, it was in the post-punk culture of the 1980s that zine culture as a scene became established. Factsheet Five, an American publication about zines, first appeared in 1982, providing a comprehensive resource for zinesters, and zine readers, to connect.

In Canada, the answer to Factsheet Five wouldn’t appear until Broken Pencil’s emergence in 1995, but in the 1980s zinesters across the country were laying a strong foundation to ensure alternative voices were heard. Consider, for instance, Ottawa fanzine No Cause for Concern? which first appeared in April, 1982. Founded by three punk and hardcore fans, NCFC ran for nine issues and, as the creators write on the zine’s posthumous website, “galvanized, lauded, created a forum for, and frequently pissed off, Ottawa’s alternative population.”

Along with disseminating information that wasn’t accessible through mainstream outlets, zines were also social vehicles that paralleled the virtual world we connect in now — although, in the 1980s, you had to make more of an effort to get connected in the first place. As Jones points out, firing off an email and getting a response minutes later doesn’t take the same commitment as writing letters, going to the post office, and waiting for a response.

“Oftentimes you’d be living in an area where you couldn’t really connect with people who were like-minded. So zines were really where the scene existed for lot of people. It didn’t exist in their town. Instead it was happening in the mail.”

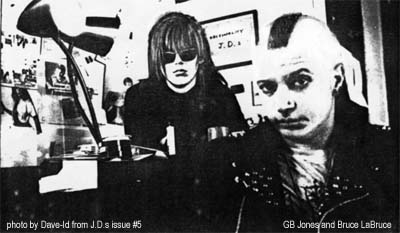

In the 1980s, zines were closing artistic and social gaps, as well as political ones. When Jones joined up with Toronto’s Bruce LaBruce to begin cutting and pasting their queer punk fanzine J.D.s (short for “juvenile delinquents”), they were doing more than appropriating found images for the collages that filled the pages alongside the stories, comics and band profiles offered in J.D.s. As LaBruce puts it, they were “reminding punk rockers that the roots of punk were actually quite queer.”

In the 1980s, zines were closing artistic and social gaps, as well as political ones. When Jones joined up with Toronto’s Bruce LaBruce to begin cutting and pasting their queer punk fanzine J.D.s (short for “juvenile delinquents”), they were doing more than appropriating found images for the collages that filled the pages alongside the stories, comics and band profiles offered in J.D.s. As LaBruce puts it, they were “reminding punk rockers that the roots of punk were actually quite queer.”

As the decade wore on, LaBruce and Jones became convinced that punk, which started with so much sexual diversity, was becoming a narrower scene as “macho” elements like hardcore moved in. Through their zine J.D.s the pair found a platform to, as Jones puts it, “question the complacency of mainstream and so-called alternative culture.” Zines gave them a voice and a place to challenge the homophobic undertones creeping into the punk scene. In February, 1989, Jones and LaBruce took that challenge to punk’s ultimate fanzine, MAXIMUMROCKNROLL, in a manifesto titled “Don’t Be Gay,” the writing of which originated from Jones’ and LaBruce’s feelings that punk had drastically departed from the sexually and socially non-conformist roots it had laid down in the 1970s. In the 1980s, and at the time when Jones and LaBruce wrote their manifesto, punk had turned to more traditional, conservative attitudes. “People read that manifesto and realized that there were all these people out there who didn’t think punk was all that great, and that it wasn’t as threatening to the mainstream as it prided itself on being,” Jones says. The manifesto was put out as a challenge to people who thought themselves to be progressive, but who were actually replicating the power structures of mainstream society by excluding non-Whites, women, queer punks and people outside established gender roles.

Jones and LaBruce received “tons and tons of letters” after the manifesto was published. Very quickly, it became clear that they had inspired a new generation of zinesters — those who felt voiceless in both the mainstream and in the counter-cultures. “It was sort of a watershed moment,” LaBruce says. “We launched a whole slew of queer fanzines. I think we were kind of acknowledged as spearheading this explosion of work.”

The ’90s

As zines moved into the next decade, they started to establish their own unique voice. Inspired by the increasingly personal tone of zines grappling with issues like sexual identity, zine creators were ever more emboldened to write about, well, just about anything. No topic was too grandiose, no subculture too obscure, and no personal issue too mundane to be unworthy of its own zine. In the early ’90s, zines were alternative culture.

“I was in a network of people who did goth zines,” says Liisa Ladouceur, writer/creator of the self-prescribed “girlie goth” zine The Ninth Wave, which ran for eight issues. “Pre-Nine Inch Nails you wouldn’t have read about any of the artists that we were writing about in pretty much any mainstream media. This was not just pre-Internet, also pre-Lollapalooza, before alternative culture got taken to the masses.”

And taken to the masses it was. When grunge crept into suburban living rooms everywhere, the mainstream suddenly perked up and started paying attention to what the underground was up to. Zinesters were interviewed on television and could sell their publications in big chain stores like the then dominant Tower Records and, with persistence, even big chain bookstores like Chapters.

“I am divided as to whether or not I think zines are meant to be underground”

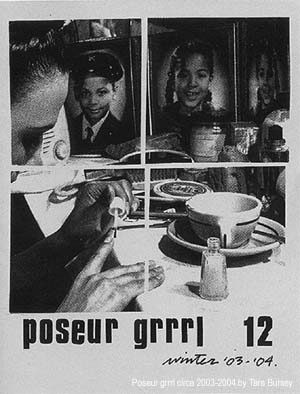

“I am divided as to whether or not I think zines are meant to be underground,” says Tara Bursey, who started making zines when she was 12 and has continued to this day. “If it weren’t for zine-making becoming a mainstream phenomena in the ’90s, I probably wouldn’t be a zine-maker of 15 years right now. Punk and zine culture reached kids at high schools in Scarborough in the ’90s, and I’m grateful for that. In the years that zines were making the news, I think youth outside of urban centres realized that they could become media producers and form their own creative communities that encompassed not just music-making, but the production of related art and written output.”

“There was a spotlight period in the ’90s with the popularity of Factsheet Five, [and] the emergence of Broken Pencil and other zine-review magazines and a few very well known zines like Dishwasher, Thrift SCORE, Answer Me!, Murder Can Be Fun and others,” says Louis Rastelli, publisher of the Montreal-based Fish Piss. “As often happens in the underground, the spotlight moved on to other things but the underground scene just went back underground.”

Despite all the extra attention they were getting, zines were bridging the same gaps they were 10 years before, helping people connect and share information.

But things were also starting to change in the ’90s. The Internet was on its way to becoming The Next Big Thing. And some zinesters and alternative publishers also had bigger ambitions.

“I stopped doing my zine when the Internet came around, and I don’t think I’m alone in that,” Ladouceur says. “Also there were new independent magazines, like BUST, that came up that started covering some of the same artists I would be writing about.”

Ladouceur says she was drawn to the cut-and-paste process of zine making, and the mail order networks involved. But when technology became a bigger part of zine culture and zines were starting to look more like magazines, she lost interest.

The ’00s

As the ’90s wound down and we moved into the ’00s, high speed Internet became the norm and self-publishing suddenly had a whole new medium. Fanzines could translate into fan sites and MySpace pages. People opened Live Journal accounts, started blogs, found each other on Facebook and started sharing updates on Twitter. Fact Sheet Five, Broken Pencil’s U.S. counterpart, had disappeared in 1998, and though its eventual return was rumoured, it never materialized beyond an infrequently updated website. And in 2007, the long-running Chicago-based zine Punk Planet folded after the release of its 80th issue. In Canada, Broken Pencil staffers saw the number of zines submitted for review decline throughout the decade.

Despite the zine’s declining population, the medium has yet to disappear — and same goes for its appeal. Take Vancouver’s Mongrel Zine as an example. Founded by Janelle Hollyrock and Bob Scott, Mongrel is a photocopied, stapled zine that features interviews and music reviews, and comes with a compilation CD. It first went to print in 2008.

“The people who read and contribute to our particular printed zine tend to be those who are actually involved in what we’re writing about,” Scott says. “Mongrel is a good way to express ourselves as the content is partly autobiographical, and the bands we interview really open up to us. We’ve taught ourselves fanzine code and etiquette by reading great Canadian zines of the past, [like] What Wave [and] Fish Piss. Their pages house time capsules of key moments in subcultural history. Good content is timeless. You can always gain some juicy or insightful knowledge when you read a good zine, no matter how old it is, and no matter how many times you’ve read it. We support the scene by producing a zine that has hours of reading material while being irreverent but also informative.”

Two years after Mongrel’s debut, Vancouver weekly The Georgia Straight celebrated the release of Mongrel’s ninth issue in late 2010, describing the local zine as “defiantly old” before asking: “Why publish a zine these days?”

“To have something tangible, to hold, and to read on the can,” Hollyrock told The Straight. “This isn’t something we thought about when we started, but it also gets more respect than a blog.”

“I’m baffled at any notion that people should stop making zines,” says Rastelli, whose Fish Piss inspired Mongrel. “Expressing yourself on your own, when no other media around you is reflecting your reality, will always be pertinent. This isn’t being replaced by Facebook or Twitter or blogs, because those are very fleeting, ephemeral expressions, and rarely involve the care one takes when deciding what to write down for posterity in a zine. If you want to leave a trace of your experiences, you still need to put it down on paper or in some other physical art form.”

“In a way, zine culture is healthier today because there are individuals out there working hard to ensure that zines stand the test of time and are firmly imbedded in our cultural history”

That said, the days of buying zines at big chain stores are also over, and as independent retailers close, victims of the struggle against corporate and online competition, zines are finding fewer and fewer homes on store shelves. Readers are increasingly caught between print and digital media. Everything is available to us all the time, and we are saturated with options when it comes to what to read, learn, or do next.

“What constitutes an alternative voice in this day and age?” asks Bursey. “Everyone has a voice on the Internet. The Internet has made it incredibly easy for people to self-publish at the push of a button, and people do. They talk about their cute cat and their breakfast and their favourite bands and clothing labels and their night at the bar or their day at the park and it never ends. The cacophony of voices on the Internet is insane. How do we navigate through it all? What does it all mean? Is it meaningless? I struggle with these questions a lot.”

Some zinesters may have traded in their glue sticks for crash courses in HTML, but, of course, there are still thousands of zines being made across North America every year. And the growing consensus seems to be that those who do bother to make zines are doing so with more dedication to zine making as an art form than ever before.

Some zinesters may have traded in their glue sticks for crash courses in HTML, but, of course, there are still thousands of zines being made across North America every year. And the growing consensus seems to be that those who do bother to make zines are doing so with more dedication to zine making as an art form than ever before.

“In a way, zine culture is healthier today because there are individuals out there working hard to ensure that zines stand the test of time and are firmly imbedded in our cultural history,” says Bursey. “In the ’90s, I’m not sure that these sorts of things were thought about nearly as much. I think at that time, people really embraced the ephemeral nature of zines, to the point that many of them from that time haven’t survived.”

A flip through the last few years of Broken Pencil seems to confirm Bursey’s observation: there may be fewer zines, but they are more artfully done, more carefully composed. As well, there’s an increasing awareness of the history of zines as a medium, an awareness that suggests an acknowledgement of zine making as an ongoing and important activity, one with posterity and tradition. Says Bursey: “The key thing that I’ve noticed about zine culture in the past 10 years is that a certain amount of focus and energy has come off of the production of zines and more focus has been put on the preservation of zines and zine history through archival pursuits such as zine libraries, websites, larger distros and the publication of books that are collections of particular zine titles.”

The ’10s and beyond

As we move into a new decade, zines look like they’ll be sticking around for a while yet.

“I think fanzines are doing really well,” says Mongrel’s Hollyrock, who name-checks ongoing zines like Razorcake, MAXIMUMROCKNROLL, Roctober, and Dig It! and points to new zines like Lost in Tyme from Greece and Bananas from New York as evidence that the zine format is alive and well.

Zines are also poised to continue doing what they’ve always done, which is to inform and unite. “Zines help connect the dots,” notes Bob Scott. “Mongrel Zine reports on our local scene in Vancouver. It is, in a sense, a Canadian scene report to music and zine enthusiasts worldwide. And with other fanzines like Dig It!, they’re gold mines of info about European bands. Those European zines tend to have amazing coverage of the international scene.”

Jonathan Culp, who runs Niagara Region’s Satan Macnuggit Popular Arts, which operated as a zine and video distro until 2004 and is now a vehicle for Culp’s various media arts projects, sees zines as a vehicle to a greater sense of community offline.

“As someone who spends way too much time on the Internet, I think the opportunities for social connectivity that zines present are still strong and important — often the Internet is its own, finite community, but zines are still, potentially, a gateway to something more.”

Bursey echoes that. “Perhaps the role of the zines today is exactly the same as what it used to be. Maybe zines are still an alternative voice, or more of an alternative voice than they ever were. In an incredibly fast-paced world where we are inundated with facts, pseudo-facts, images and useless information transmitted digitally, zines are something refreshing and different.”

Today, there are more options than ever for us to communicate and connect, but indie publications are still underground, still subversive and still powerful, because they can be about whatever their creators want them to be. The Internet, beset by monitors and censors and no longer the modern-day version of the Wild West, may yet once again take a backseat to the anything-goes ethos of the zine.

The way we get our information will continue to change, especially as print media continues to find its place in an increasingly digital world. The Internet is still young and evolving, and so is a whole new generation raised on iGadgets and now just starting to discover independent culture. GB Jones says she’s been talking to kids recently who’ve told her how important the history of movements like riot grrrl and queercore is to them, and that the significance of these scenes still resonates even though they also feel those scenes have vanished. It’s as though the Internet’s virtual communities are feeling hollow, and in the real world there are fewer places where alternative communities, particularly with younger members, can unite to question, challenge, or just connect — the way people have been doing on paper, and in the mail, for years. “I think those kids feel a need to recreate that kind of scene,” Jones says. “And because of that, I think zines are more important than ever.”